I wanted to follow up my earlier posts about teaching the Vietnam War with sample readings, including some original translations. (See the full sample syllabus here and here for more detail.) In the box below is the journal prompt and readings about communism and republican nationalism that I assign for week 2 of the course as well as my notes. Following that are the first three readings, all of which are excerpts. I usually combine these excerpts into a single handout.

2. Different Paths to Independence

*Hồ Chí Minh, “Appeal Made on the Occasion of the Founding of the Indochinese Communist Party,” from http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/ho-chi-minh (excerpt)

*Tố Khanh, “Class Struggle or National Struggle?” (excerpt) [my original translation]

*Huỳnh Phú Sổ, “The Way to Practice Religion and Rules for Everyday Life,” in Sources of Vietnamese Tradition (excerpt)

Nguyễn Công Luận, Nationalist in the Vietnam Wars, xiii-xv, 3-10, 11-44 (recommended: 45-60)

Journal prompt: Imagine that the peasants that we read about last week in Phi Vân’s The Peasants were presented with the documents by Hồ Chí Minh, Tố Khanh, and Huỳnh Phú Sổ. Which document(s) would appeal to the peasants and why? Which one(s) would they disagree with and why? According to Nguyễn Công Luận, why did people support the Việt Minh in 1945?

My notes: The second week examines the disagreements among various Vietnamese who championed independence, especially the cleavage between communists and republican nationalists. During discussion, I ask students how Hồ Chí Minh, Tố Khanh, and Huỳnh Phú Sổ define “the people.” Although The Peasants takes place specifically on the Cà Mau Peninsula, I use that reading to discuss peasants in the Mekong delta more generally and how the southern peasantry responded to different political factions. I also ask students to consider which documents Nguyễn Công Luận would find appealing and how his portrayal of northern Vietnamese society differs from the society of the Mekong delta described in The Peasants.

SAMPLE READINGS: PRIMARY SOURCES ON COMMUNISM AND REPUBLICAN NATIONALISM IN COLONIAL VIETNAM

A. Appeal Made on the Occasion of the Founding of the Indochinese Communist Party (Hồ Chí Minh, Vietnamese,1930), from http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/ho-chi-minh/

The Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) was Vietnam’s first and most significant communist party during the colonial period. Hồ Chí Minh, an ardent nationalist and dedicated communist, established the ICP in 1930 by unifying multiple communist factions. The party initially called itself the “Vietnamese Communist Party” but changed its name and program to encompass all of French Indochina to conform to the instructions of the Comintern, the Soviet agency that advocated world revolution. During the conference, Hồ drafted the party’s official appeal, excerpted below. The appeal called for a social revolution against French colonialism, Vietnamese feudalism, and the “comprador bourgeoisie,” that is, the indigenous middle class.

The revolution [being carried out by the communists] has made the French imperialists tremble with fear. On the one hand, they use the feudalists and comprador bourgeoisie to oppress and exploit our people. On the other, they terrorize, arrest, jail, deport and kill a great number of Vietnamese revolutionaries. If the French imperialists think that they can suppress the Vietnamese revolution by means of terror, they are grossly mistaken. For one thing, the Vietnamese revolution is not isolated but enjoys the assistance of the world proletariat in general and that of the French working class in particular. Secondly, it is precisely at the very time when the French imperialists are frenziedly carrying out terrorist acts that the Vietnamese Communists, formerly working separately, have united into a single party, the Indochinese Communist Party, to lead the revolutionary struggle of our entire people.

Workers, peasants, soldiers, youth, school students!

Oppressed and exploited fellow-countrymen!

The Indochinese Communist Party has been founded. It is the Party of the working class. It will help the proletariat lead the revolution waged for the sake of all oppressed and exploited people. From now on we must join the Party, help it and follow it in order to implement the following slogans:

- To overthrow French imperialism and Vietnamese feudalism and reactionary bourgeoisie;

- To make Indochina completely independent;

- To establish a worker-peasant-soldier government;

- To confiscate the banks and other enterprises belonging to the imperialists and put them under the control of the worker-peasant-soldier government;

- To confiscate all the plantations and property belonging to the imperialists and the Vietnamese reactionary bourgeoisie and distribute them to the poor peasants;

- To implement the 8-hour working day;

- To abolish the forced buying of government bonds, the poll-tax and all unjust taxes hitting the poor;

- To bring democratic freedoms to the masses;

- To dispense education to all the people;

- To realize equality between man and woman.

B. “Class Struggle or National Struggle?” (Tố Khanh, 1946), original translation by Nu-Anh Tran

The Vietnamese Nationalist Party (Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng, VNP, or Việt Quốc) was Vietnam’s first modern political party. Founded in 1927 by Nguyễn Thái Học, the party adopted the political philosophy of the Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen. By the mid-1940s, the party was locked in a fierce competition with the Vietnamese communists and grew increasingly critical of communist ideology. The excerpt below is taken from an article published in the official newspaper of the VNP. The author Tố Khanh, whose exact identity remains unknown, contends that communism is unsuitable for Vietnam and displayed remarkable familiarity with Marxist ideas.

Communists who want to implement their ideology say that class struggle is the means to break the chains of slavery that bind our country. Workers and tillers must guide the present revolution. [The communists say that it is necessary to] struggle against the capitalists, destroy them, and oppose the imperialists. The communists want to copy and recreate Russian history, that is, to redo the disastrous experiment that took place in that country after the revolution of October 1917. We must ask ourselves whether we should take such an action, and if not, we must find a different principle upon which to act.

We must understand that the social and economic conditions in our country are not like in the European countries that Karl Marx observed to construct the ideology of communism. Moreover, our country is not fully autonomous, and this political situation creates many difficulties for the present revolution.

According to Karl Marx, there will be two events [sự kiện] in a capitalist society: first, the concentration of capital, and second, the impoverishment of the masses. The concentration of capital causes a group of property-owners [hữu sản] to hold all the privileges in society, and the remainder [of the population] are all proletariats [vô sản] that must endure misery. This situation leads to a struggle between two opposing classes [gai cấp tương đối], the propertied and the proletariat, and the result is that the propertied will be annihilated, and the proletariat will become dictatorial.

Have those predictions been realized? In Europe and America, the concentration of capital has advanced greatly in the economy and in commerce. Then has the concentration of capital led to the formation of two opposing classes? Karl Marx’s prediction was incorrect on this point, for the societies of capitalist countries have not split into two completely separate classes but have instead split into many classes, and capitalist societies even have middle classes. That is in regard to countries that have been organized according to new economic principles and in which the concentration of capital is an actuality. As for our country, there are several factories and several railroads, but they do not belong to us but to [foreigners] [missing text] Agricultural land is divided among innumerable people, and there are few landlords and landowners. Then where can there be found two opposing classes so that one may advocate for class struggle? All people in our country live in poverty and misery, and those that are called wealthy are merely somewhat poor.

The communists are very mistaken to advocate that the laboring class initiate the revolution. The laboring class is not the only one that suffers. It is the whole nation that is mired in poverty because of a foreign country and that must rise up in revolution. The entire nation suffers due to imperialism regardless of class. The demands of workers and tillers are valid but should not be used to pin the blame on the propertied and the few landowners in our country. We must struggle against foreigners. The petty bourgeoisie is also destitute, and again that is because the economy is under foreign control. In sum, all classes must struggle together in the interests of the nation [dân tộc]. In this anti-imperial struggle, workers, tillers, and the bourgeoisie must shed their blood together in order to build up the nation [gây dựng quốc gia]. To slaughter each other through class struggle at this moment would be an egregious error and a betrayal of national interests [quyền lợi dân tộc] because it will only fragment the force of the people.

C. “The Way to Practice Religion and Rules for Everyday Life” (Huỳnh Phú Sổ, 1945), from Sources of Vietnamese Tradition, 439-441

The Hòa Hảo was a new Buddhist movement founded in 1939 by the charismatic Huỳnh Phú Sổ in the western Mekong Delta. The religion grew out of a century-old tradition of Buddhist millenarianism as well as the 1930s Buddhist revival movement, and it also was based on religious practices prevalent among the southern peasantry. In the 1940s, Sổ systematized Hòa Hảo precepts, emphasizing home worship, simple Buddhist rituals, and the “Four Gratitudes.” This text, written in 1945, demonstrates Huỳnh Phú Sổ’s strong emphasis on national affairs and concerns for the world at large.

Gratitude to Our Ancestors and Our Parents

We are born with a body to be active from childhood and to adulthood and [our parents nurture] us in wisdom and knowledge. Do we realize how much our parents have sacrificed for all these years? [Remember that] our ancestors gave birth to our parents and that we should be grateful to our ancestors as [much as] we are grateful to our parents.

To show our gratitude to our parents, we must learn from the good things they have taught us and must not cause them any trouble. If our parents did anything wrong or acted against ethical principles, we should do our best to advise and prevent them from doing so. We also should support them and keep them from hunger and illness. To please our parents, we should strive to achieve harmony among our brothers and sisters and to bring happiness to our family. We pray for our parents to enjoy happiness and a long life. When they die, we pray for their souls to be freed from suffering in the land of the Buddhist kingdom.

To show our gratitude to our ancestors, let us not do anything wicked or that would bring shame to our family name. If our ancestors did anything wrong, or left a legacy of suffering to their descendants, we should dedicate ourselves to acting in accordance with moral principles in order to restore our honor.

Gratitude to Our Country

Our ancestors and our parents gave birth to us, but we owe our living to our country and our native land. Because we enjoy the fruits of our land, it is our duty to defend our country if we want our life to be sustained and our race to survive. Let us help safeguard our country, making it strong and prosperous. Let us try to liberate our country from foreign domination. We are safe only when our nation is strong and wealthy.

…

Gratitude to Our Fellow Countrymen and Humanity

From the day we are born, we are dependent on those around us, and as we grow up, this dependence increases. We need other people to produce the rice that feeds us, the clothes that keep us warm, and the houses that shelter us from storms. We share happy times and misfortunes with them. We and they have the same skin color and speak the same language. Together we form a nation. Who are these people? They are those we call our fellow countrymen. We and our compatriots come from the same race, have the same illustrious and heroic history, help one another in distress, and have the common task of building a bright future for our country. We have a close relationship with our compatriots, are indivisible, and cannot be detached from one another. We would never be where we are without them. Therefore, we must do our best to help them and show them gratitude in some way for the assistance we have received from them.

FULL BIBLIOGRAPHIC CITATIONS FOR THE EXCERPTS

Tố Khanh. “Giai Cấp Tranh Đấu hay Dân Tộc Tranh Đấu.” Chính nghĩa 3 (3 June 1946): 11.

Huỳnh Phú Sổ. “The Way to Practice Religion and Rules for Everyday Life.” In Sources of Vietnamese Tradition, 439-441. Edited by George Dutton, Jayne Werner, and John Whitmore. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Hồ Chí Minh. “Appeal Made on the Occasion of the Founding of the Indochinese Communist Party.” Marxists Internet Archive. Last modified 2003. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/ho-chi-minh/works/1930/02/18.htm.

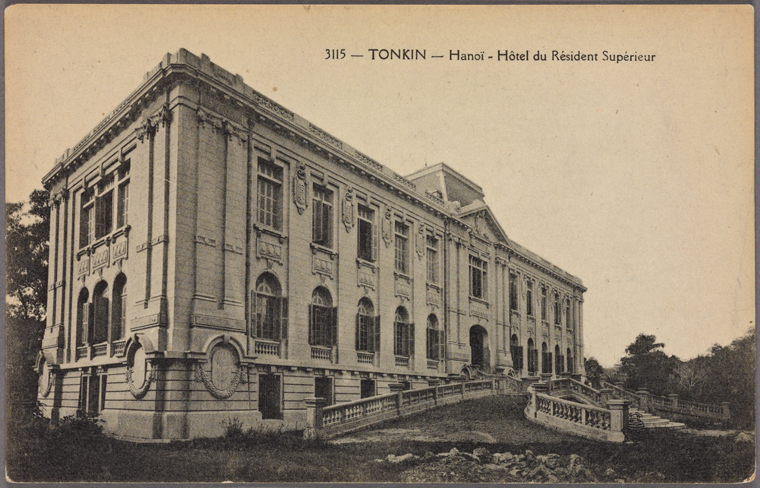

Photo credit: The postcard image linked to this post shows the Hôtel du Résident supérieur of Tonkin. The French divided Vietnam into three administrative regions, and Tonkin was their name for northern Vietnam. The résident supérieur was the highest executive office of the French colonial administration in Tonkin. I believe the building featured in the image served as both the administrative office and official residence of the résident supérieur. You can find the image here: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/c263504a-1986-b3d1-e040-e00a18061791