Phạm Duy’s “Riddles” (“Đố ai,” 1954?) is a charming song that mixes tradition and modernity. It is the last track on Saigon Rock & Soul, and this post will probably be my last one in my series-within-a-series translating the lyrics of songs from that CD.

“Riddles” exemplifies a Vietnamese musical genre known as “new folk music” (dân ca mới) or “arranged folk music” (dân ca cải biên), that is, modern songs that composers arranged based on traditional Vietnamese folk music. The traditional music that inspired “Riddles” would have been songs that young villagers sang during riff off contests. Young people divided into groups based on gender, and men and women took turns challenging each other by performing songs on the same theme or with similar recurring phrases. They spontaneously composed lyrics to best each other at wordplay, though the tune often followed an existing formula. These singing challenges could often get flirtatious as the singers teased each other with romantic lyrics.

True to its origins, “Riddles” begins with a series of riddles drawn from folk music and folk poetry. The riddles evoke the village world of rivers, clouds, forests, wind, and rice fields, and it’s easy to imagine young men and women trying to stump each other with these questions. The last verse suddenly turns romantic, and the chorus is mildly provocative. Although the wording is ambiguous, I think the chorus describes a midnight tryst between the male narrator and his female beloved. (The pronouns indicate the gender of the narrator and his interlocutor.) The tryst begins with uncertainty, as the narrator waits like “the setting moon wait[ing] under the eaves outside” (trăng xuống đứng chờ ngoài hiên). But in the very next line, he initiates an encounter and quickly “reaches the shore of love” (đến bến bờ yêu đương). The couple fondle each other in the darkness, and the lyrics describe them as searching for each other’s hearts (Đố ai tìm được tim ai). In the end, the narrator is overcome by romantic and sexual bliss, and he offers his beloved a heartfelt song.

“Riddles” was part of a larger move by musicians to incorporate Vietnamese folk music (dân ca) into the Western-influenced “new music” (tân nhạc), thus creating the new genre of “new folk music.” The emergence of the genre reflected migration patterns and cultural changes in mid-century Vietnam. During the last decades of the French colonial period, Vietnamese village elites moved to the cities to complete their education at the same time that poor peasants flocked to urban areas for employment. Vietnamese migrants of all class backgrounds brought their musical traditions with them, including folk songs that evoked memories of home and familiar village customs. At the same time, they also became exposed to Western-style music in the cities, and those that returned to the countryside brought those styles back home. Vietnam’s war of independence against France, known as the Resistance War (1945-1954, also the First Indochina War, with the slightly different date range 1946-1954) accelerated internal migration. Civilians fled to the countryside when French forces attacked the cities, but many went back to French-controlled urban areas during the late stage of the conflict when conditions stabilized. Large numbers of Vietnamese also migrated between different rural regions in search of safety. The greatest migration of all took place at the end of the war when Vietnam was partitioned into two zones, and over 800,000 people moved from the northern to the southern zone (which I discussed in my post about Phạm Đình Chương’s “Springtime in Exile”). The urban-rural circulation created an intermixing of old and new as well as Western and native, and musicians composed and arranged music that captured the sensibilities of Vietnamese who still thought fondly of their village home but whose tastes had been transformed by their residence in the cities.

Phạm Duy is the most important Vietnamese musician of the twentieth century, and “Riddles” was part of this musical trend. He started arranging “new folk music” in the late 1940s when he was musician working for the Việt Minh, a communist-led nationalist organization that fought for independence during the Resistance War. He composed many songs in support of the independence struggle, often drawing inspiration from the Vietnamese peasantry and rural musical traditions. Like many artists and intellectuals, he left the Việt Minh after the organization abruptly imposed restrictions on art, music, and literature in 1948. He moved to Saigon and then spent the early 1950s studying abroad in Paris. Many websites indicate that “Riddles” was composed in 1954, which meant that Phạm Duy either arranged it towards the end of his studies in France or soon after he returned to Saigon. He continued his musical career in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, or South Vietnam) and later overseas after the Vietnam War (1954-1975).

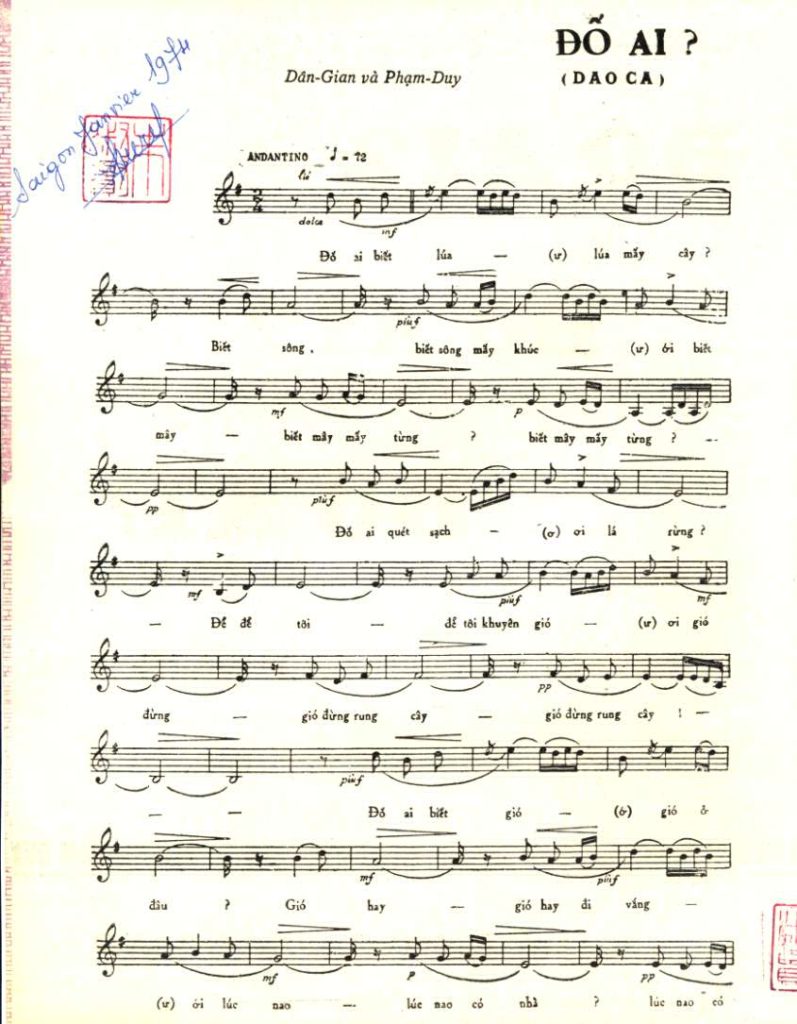

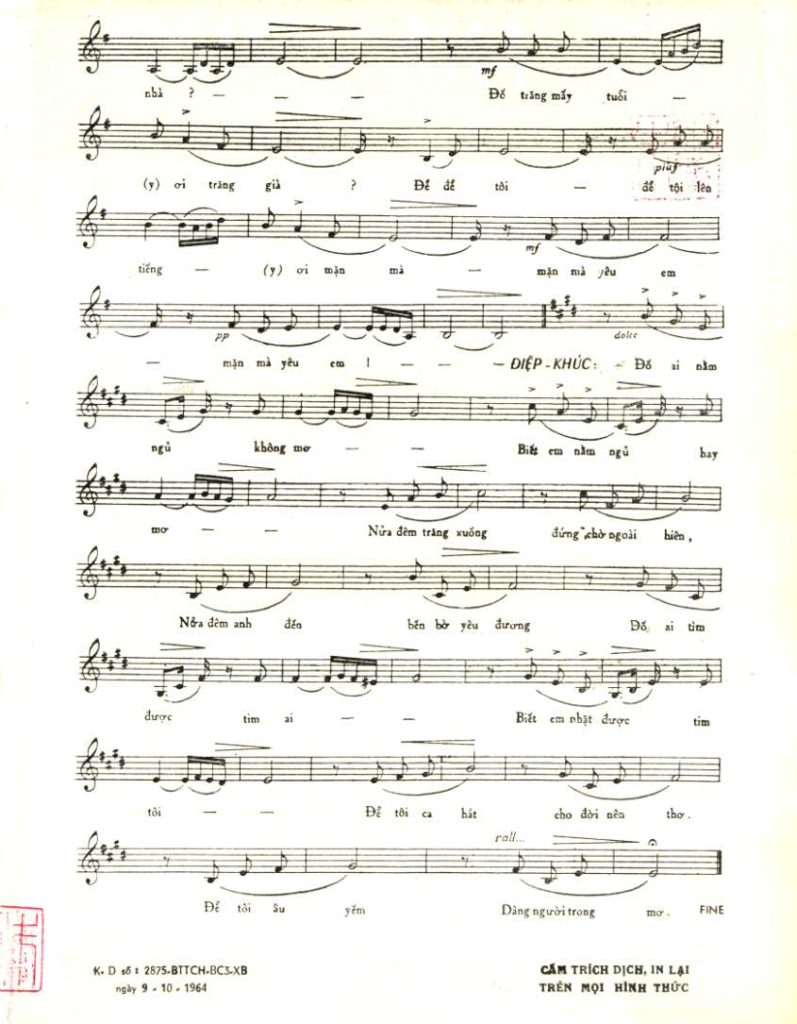

This rendition of Phạm Duy’s “Riddles” is performed by Phương Dung. The software I am using does not allow for footnotes on some posts, so they appear below my translation but are not linked. There are minor differences between the recording and the sheet music, and flourishes and changes in the CD version appears below in red to make it easier for the listener to follow along. Note that the song contains numerous non-lexical vocables that are common in Vietnamese folk music. Here, the vocables consist mostly of vowels such as ơi, ơ, ới, ư, and y. (In English-language music, common non-lexical vocables include fa la la la, la la la la, and dee dee dum.)

ĐỐ AI

Dân ca cải biên của Phạm Duy

Đố ai [ai] biết lúa – ư lúa mấy cây?

Biết sông, biết sông mấy khúc? – ư ới

Biết mây, biết mây mấy từng?

Biết mây mấy từng? [ơ ời ơ]

Đố ai quét sạch – (ơ) ơi lá rừng?

Để, để tôi – để tôi khuyên gió – (ư) ơi gió đừng

Gió đừng rung cây,

Gió đừng rung cây! [ơ ời ơ]

Đố ai biết gió – (ớ) gió ở đâu?

Gió hay – gió hay đi vắng – (ư) ới lúc nào

Lúc nào có nhà,

Lúc nào có nhà? [ơ ơi ơ]

Đố trăng mấy tuổi (y) ơi trăng già?

Để, để tôi – để tôi lên tiếng – (y) ơi mặn mà

Mặn mà yêu em,

Mặn mà yêu em! [ơ ơi ơ]

Điệp khúc:

Đố ai nằm ngủ không mơ [ơ ơi ơ]

Biết em nằm ngủ hay mơ [ơ ơi ơ]

Nửa đêm trăng xuống đứng chờ ngoài hiên,

Nửa đêm anh đến bến bờ yêu đương.

Đố ai tìm được tim ai

Biệt em nhặt được tim tôi

[CD version]: Biết em tìm được tim tôi… ơ ơi ơ

Để tôi ca hát cho đời nên thơ.

Để tôi âu yếm dâng người trong mơ.

RIDDLES

Traditional folk music arranged by Phạm Duy

Original translation by Nu-Anh Tran

Who could tell me ah tell me how many stalks of rice there are?

How many, how many stretches has a river? Ah oh…

How many, how many layers has a billow of clouds?

How many layers has a billow of clouds? Oh oh oh…

Who could sweep away, oh sweep away all the leaves in the forest?

Let, let me, let me counsel the wind not to, ah oh not to…

Not to shake the trees,

Not to shake the trees! Oh oh oh…

Who could tell me where the wind, oh where the wind is?

The wind, the wind is often away, ah oh and when…

When is it ever home,

When is it ever home? Oh oh oh…

Who could tell me the age oh the age of a waning moon?

Let, let me, let me say how passionately, ah oh how passionately…

How passionately I love you,

How passionately I love you! Oh oh oh…

Chorus:

Who could sleep without dreaming? Oh oh oh…

Knowing that you dream often in your sleep oh oh oh…

In the middle of the night, the setting moon waits under the eaves outside,

In the middle of the night, I reach the shores of love.

Who can find whose heart? Oh oh oh…

Knowing that you can find my heart… Oh oh oh…

Let me sing to make life more poetic,

Let me tenderly offer [my song] to the one in my dreams.1

Notes

1The original lyrics are somewhat ambiguous as to what the narrator is offering the person in his dreams. I believe the narrator is offering his song to his beloved, but it is possible that he is offering to spend his life with her.

THE TECHNICAL STUFF

The original sheet music can be found here: https://hopamviet.vn/sheet/song/do-ai/W8IUIUEU.html

The period recording can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vWCeMggn8iM

Image credit: https://www.sublimefrequencies.com/products/576864-saigon-rock-soul-vietnamese-classic-tracks-1968-1974

Translating khúc as reach doesn’t seem impossible, but it also doesn’t feel right. It’s a technical term not a popular term – https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/what-a-reach

I think the word stretch works better.

Biết sông, biết sông mấy khúc?

Do you know the river, know the river has how many stretches?

Nice translation!

Good point! That line was a tough one for me. Perhaps this would be better: “How many stretches has a river? Ah oh…” Just made the change.