Nguyễn Thanh Trịnh’s What If We Were in Love (Ví dụ ta yêu nhau, 1974) is a clever frame narrative about romantic love set in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, or South Vietnam). The book starts with a letter from an unnamed young man urging his love interest, Nhỏ, to imagine that they are in love. To inspire her imagination, he writes her ten love stories that can serve as examples (ví dụ) for them to emulate. These love stories make up the heart of the novel, and they read like long, loosely connected vignettes that are vaguely reminiscent of the letter writer and Nhỏ. Similar to the letter writer, the narrators of the love stories are unnamed young men. The narrators in their twenties and typically serve in the military or work as schoolteachers. Their various love interests are obviously stand-ins for Nhỏ. Not only are many of these female characters named or nicknamed Nhỏ, the narrators often describe the objects of their affection as nhỏ, meaning “young” or “small,” or em nhỏ, meaning “little miss.” And, indeed, the love interests are rather young, mostly teenage schoolgirls and schoolmates. Twenty-first century readers will undoubtedly find the age difference creepy, but it was apparently social acceptable at the time.

Yet the vignettes are not directly about the central couple. In fact, it’s not even clear whether the stories are about different men or represent various moments in the life of the same man, though the vignettes do follow a general arc. In the earlier stories, the narrators are immature and driven by their voracious hunger for food, affection, and love. They recount their romantic adventures with sarcasm and humor and are able to laugh at themselves. In the later stories, thwarted love and broken relationships have rendered the narrators sadder and wiser. These young men express frustration and longing, and the overall effect is wistful rather than comical. It is as if the letter writer is demonstrating to Nhỏ his emotional maturation over the course of the novel.

With each passing story, the reader (and perhaps Nhỏ as well) increasingly wonders if the letter writer is making up these stories or drawing from real life. Although he adamantly assures her that these examples are not about him, it’s hard to believe him fully as the stories are so emotionally rich. Moreover, the narrators of the earlier vignettes are prone to using the Catholic epithet, “Oh lord!” (“Chúa ơi!”) just like the letter writer. But then again, if he’s trying to get Nhỏ to date him, would he really tell her about all of his exes? It’s worth noting that the young couples in this novel, set in the early 1970s, enjoy almost complete freedom to become acquainted and go on unchaperoned dates. They are even freer than the Saigon youth in Nhã Ca’s At Night I Hear the Cannons (Đêm nghe tiếng đại bác) from the mid-1960s and worlds away from the young women of Bình Nguyên Lộc’s Thoroughfare (Đò dọc) in the late 1950s. Although three novels hardly constitutes a sufficient evidence, the books do track with historical patterns of loosening social mores over the course of the RVN’s existence.

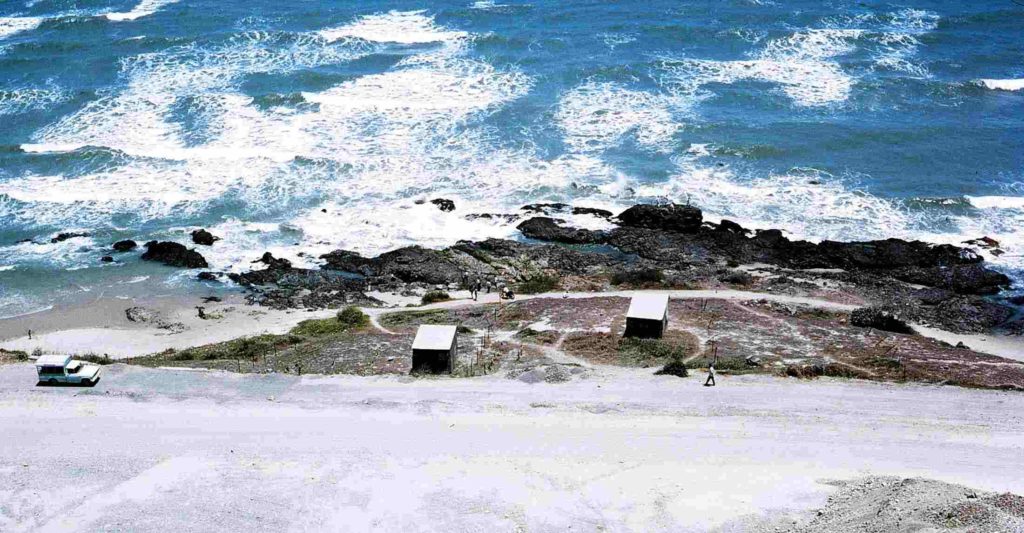

I enjoyed quite a few of the love stories, especially the light-hearted vignettes at the start of the book. My favorite was the first story in which a soldier falls for the teenage sister of one of his comrades when she visits her brother at the military camp in Vũng Tàu on the southeastern coast. It is the narrator’s task to distribute the dinner rations, but because she has wandered off, he is forced to search for her on the beach even as his own stomach is growling. When he finally finds her, she coolly informs him that she is not hungry and that she did not need his permission to wander off since she had no intention in partaking in the rations. The narrator is annoyed. He then tries to persuade her to return to the camp for fear that something may happen to her if she stays on the beach alone at night. She bluntly refuses. Again annoyed, he feels he has little choice but to wait with her until she is ready to return of her own accord.

On the way back to camp, the two engage in flirtatious banter, and I found myself laughing out loud. He starts by asking her exasperatedly, “Why are you obstinate as a crab?” (“Sao em ngang như cua vậy,” 23). In Vietnamese, ngang literally means horizontal or sideways. The word also has a second meaning of being “obstinate,” “stubborn,” or “contrarian” and describes someone that refuses to conform to the straight, vertical axis and instead does whatever he or she pleases. The idiomatic expression “obstinate as a crab” plays on both meanings of the word: a crab crawls sideways by nature just as a person might be stubborn by nature. The narrator’s admonishment prompts the teenage girl to reply haughtily, “That’s just my personality, so everyone hates me, and I don’t care for anyone either” (“Tính tôi vậy đó nên ai cũng ghét tôi và tôi cũng chẳng yêu ai,” 23). But the narrator counters, “Yes, except for me because I really like to eat crabs, especially salted, toasted crab” (“Phải, trừ tôi ra vì tôi rất thích ăn cua, nhất là cua rang muối,” 23). She has no interest in letting him win and replies with her own witticism, “You are obstinate as a crab too. I’m just a field crab but you’re a sea crab” (“Ông cũng ngang như cua. Tôi chỉ là cua đồng còn ông là cua biển,” 23). Both sides have met their match.

Unfortunately, the later love stories were overly sentimental and did not live up to the promising start of the first one, though I did find some of them intriguing for their unusual settings or characters. The third story is about a disabled veteran who arrives in Phan Rí on the south central coast to work as the secretary of a fish sauce factory and falls for a local girl. I’m not sure I’ve ever read any piece of literature that juxtaposed romantic love with Vietnam’s pungent national sauce! It rather reminds me of ee cummings’ “rish and foses.” The sixth story proved even more surprising, and I actually did a double take when I read that the narrator’s girlfriend is a teenage boxer. A boxer? Not only that, she’s an athletic prodigy who is favored to win the national junior division in the Republic of Vietnam. What a creative choice on the part of the author to give the narrator a love interest that engages in an aggressive, hypermasculine sport.

Finally, the ninth story caught my attention because it confirmed much what I wrote earlier about Christmas celebrations in Saigon. The narrator is a non-Catholic teacher at a Catholic school and receives a visit from an old girlfriend over the holiday break. In keeping with the tradition of réveillon, the couple stroll through downtown Saigon on Christmas Eve to enjoy the festive atmosphere. (There’s even a reference to a réveillon cake, most likely a French bûche de Noël.) Yet the narrator doesn’t seem to appreciate the celebration. He glares witheringly at the revelers blowing party horns outside of Nôtre Dâme Cathedral (Nhà Thờ Đức Bà) and disapproves of the seemingly rushed and unenthusiastic religious service. Instead, he remembers the sincere but humble midnight mass he witnessed in a poor neighborhood in Đà Nẵng.

One of the unifying threads running through these love stories is that the narrators expect their love interests to be sweet, demure, and passive but are surprised that the opposite sex can be assertive, stubborn, and independent. In several stories, the young men try to get their love interests to change or obey but to no avail. The obstinate-as-a-crab girl ignores the soldier’s orders at Vũng Tàu, and he is forced to submit to her will rather than the other way around. An officer in a sleepy central Vietnamese town warns a schoolgirl to cut back on reading because it is unattractive for girls to be nearsighted. She shrugs off his advice by pointing out that she already wears glasses and refuses to give up her books (78). The above mentioned boxing champion’s boyfriend urges her to quit the sport for fear that she is too aggressive to ever find a husband. Although she ultimately decides to leave boxing behind, she does it for her own reason and even warns him that she’s still strong enough to break his heart (122-123). Interestingly, it is often the female characters that are in control of the relationships. A schoolgirl pushes her older, sickly boyfriend to make plans to marry her (140-141), and a college student abruptly breaks up with her classmate when he acts irrationally jealous (44). These strong women and girls frustrate their admirers precisely because they defy traditional gender expectations, and the newly single narrator in the seventh story seems to speak for many of the other narrators when he proclaims that the opposite sex can make good friends but are poor lovers because women and girls are fickle (129). With this comment, is Nguyễn Thanh Trịnh revealing his own sexism or criticizing the sexist expectations of his male narrators? It’s ambiguous.

Upon reflection, it occurs to me that it is the vividness of the female characters that makes this book fun to read. The women and girls who appear on these pages have a strong sense of self and distinctive tastes and hobbies. Their actions often drive the plot, and they are more likely to grow and change over the course of the stories. In contrast, the narrators have poorly defined personalities and often twist themselves into a pretzel to please their love interests. I finished the book feeling like I really knew the female characters but could barely distinguish the narrators from one another, with few exceptions, despite being given direct access to the narrators’ emotional interiority. The discrepancy almost begs the question: Why would any of these interesting women and girls want to date such bland men?

The reader can only guess what Nhỏ thinks of the letter writer after hearing ten love stories, but the closing letter suggests that he like the narrators is also surprised to discover that his crush has a will of her own. The unnamed narrator urges Nhỏ to get closer to him and asks suggestively, “What if we were to get married?” (“Ví dụ ta lấy nhau thì sao?” 194). She apparently finds him too forward, and the novel ends with her suitor’s shocked exclamation: “Oh lord! Why did you just bite my ear off?” (“Chúa ơi! Sao em lại cắn đứt tai tôi?” 194).

TECHNICAL STUFF

Note for readers: Nguyễn Thanh Trịnh’s What If We Were in Love is available online in Vietnamese at https://www.vietmessenger.com/books/?title=vi%20du%20ta%20yeu%20nhau. The author also wrote under the alternative pseudonym Đoàn Thạch Biền.

Note for researchers: This novel would be great for scholars interested in gender, courtship, and urban youth culture in the RVN. In addition to some of intriguing settings and scenarios described above, I wanted to mention two more that might be useful for researchers. In the sixth love story, the teenage boxer trains with a Filipino coach, and the boxer and her boyfriend grab dinner from a Chinese food vendor. Chinese characters are not uncommon in Vietnamese literature, but this is the first time I’ve seen mention of a Filipino character. The second story features a hilarious depiction of a philosophy lecture at a university in Saigon and pokes fun at the popularity of philosophy among young, urban, educated Vietnamese.

The version I read: Nguyễn Thanh Trịnh. Ví dụ ta yêu nhau. Reprint ed.Houston, TX: Saigon Co., [nd].

Image credit for book cover: https://vietmessenger.com/books/?title=vi%20du%20ta%20yeu%20nhau

Credit for featured image: The featured image at the top of the post shows Vũng Tàu in the 1970s, which is the scene of the first vignette. I found the image here: https://saigoneer.com/vietnam-heritage/15431-photos-vung-tau-in-1970-bars,-beaches-and-bustling-bazaar-2.