Nguyễn Mộng Giác’s One-Way Street (Đường một chiều, 1974) is an absolute page-turner. Set in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, or South Vietnam), the novel starts with the shocking murder of Thúy while her husband Major Lộc is away fighting in the Central Highlands as part of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. There’s no question as to who killed her. The culprit is clearly Corporal Ninh, Lộc’s trusted subordinate, but no one can figure out Ninh’s motive. Lộc, a paratrooper officer, cannot fathom how the good-natured Ninh could commit such a heinous act. The military police, the prosecutor, and the defense lawyer struggle to make sense of the crime as well. Even Ninh does not fully understand why he did it. Ultimately, what the investigation and trial reveal is the impossibility of truly knowing either the murderer or the victim.

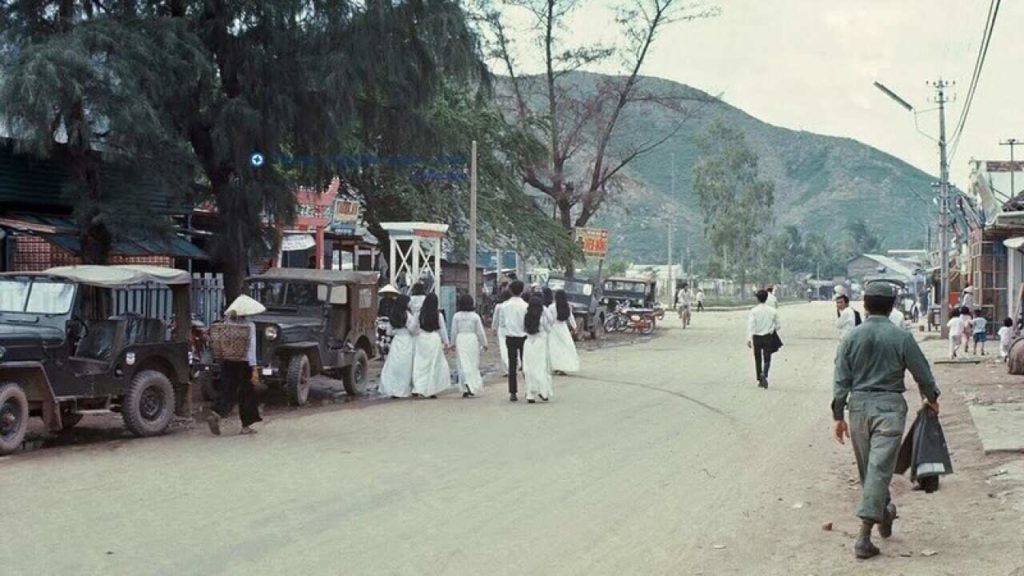

One-Way Street reads like a cross between a legal drama and a psychological novel. Although the trial occupies the bulk of the book, the twists and turns come from the characters’ turbulent thoughts and emotion rather than from courtroom maneuvers. Major Lộc is the narrator, and it is through his eyes that the story unfolds. We learn the basic facts of his family through flashbacks. He married Thúy seven years earlier, probably around 1965, and the newlyweds settled in an unnamed city on the central coast, possibly Qui Nhơn. He accepted his wife’s daughter from a previous relationship as his own, and the happy couple had several additional children. The major and his wife were especially fond of his driver, the gentle and intelligent Corporal Ninh, and welcomed the young soldier into their family circle. Before leaving for the front in the Central Highlands, Lộc specifically selected Ninh from among his men to remain at the rear base and handle logistics and supplies for the battalion. Ninh is grateful for the favor and frequently runs errands for Thúy and entertains the children. That is the glowing portrait of domestic harmony and comradeship that Lộc paints for the military police chief who investigates the murder.

So it comes as a shock to Lộc when he learns that Ninh killed his wife. The death shatters Lộc’s domestic bliss and forces him to question everything he thought he knew about the people closest to him. He feels especially torn between his love for his wife and his fondness of Ninh. Is the prosecution right that the corporal intended to rape and murder Thúy? Or is the defense correct that Ninh came home and was surprised to be seduced by Thúy? Lộc does not want to believe that his protégé is a cold-blooded murderer. Neither does he want to suspect his wife of infidelity, but he cannot help but wonder after he learns that his wife had a past she never shared with him.

The loss of Thúy brings Lộc closer to his sweet, sensitive stepdaughter Ly, but he starts to believe that Ly may have secrets of her own too. Ly is the only witness to the murder and seems more affected by her mother’s absence than any other character in the novel. Yet why is she so reluctant to testify in court and clear her mother’s name? Who is her father and what sort of relationship did the girl have with Ninh? Like Lộc, the reader gradually learns that none of the characters are exactly what they seem.

One of the central themes of the novel is the voyeurism of a public trial. The murder is a tragedy for Lộc’s family but entertainment for the general public. Spectators eagerly fill the gallery as if they are attending a show. They stare intrusively at Lộc and his children and lap up every juicy detail about Thúy’s death. This sense of justice-as-entertainment is heightened by the theatricality of the proceedings. The trial takes place in an old theater rather than a courthouse due to construction, and the spectators are literally audience members watching a trial take place on stage. When the judge does a roll call of the witnesses, it functions as an introduction to the dramatis personae. Each witness that comes to the stand has a distinct way of speaking that defines his or her character: the hesitant and remorseful Ninh, his plainspoken father, Ninh’s smooth-tongued drinking buddy, anxious little Ly, the indignant Major Lộc, and the dispassionate medical examiner. Not only does the novel indict the spectators for their voyeurism, it suggests that the reader is complicit too because we are also entertained by this gripping story.

Lộc’s chaotic home forms a contrast to the (mostly) orderly courtroom. Thúy was a capable mother and housekeeper, and her death threw the family into disarray. Without her at the helm, the young children misbehave, and the household servant challenges her employers’ authority. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Lộc utterly fails in his attempts to wrangle his kids and manage the household. The mounting chaos forces the teenage Ly to step into her mother’s shoes as the lady of the house and a surrogate mother to her half-siblings, and Lộc is both amused and touched by the girl’s precocious sense of responsibility.

One-Way Street is one of the most carefully crafted books I have ever read. Thúy’s death is a singular episode that puts into motion a chain reaction, with each event triggering the subsequent one and every revelation foreshadowed but not revealed. It is this combination of anticipation and inevitability that makes the book so suspenseful. The name of the book suggests an inescapable, unidirectional course of events and evokes a sense of foreboding. I think the implication is that is impossible for Lộc or anyone else to prevent the violence, destruction, and despair wrought by the murder. What I find especially remarkable about Nguyễn Mộng Giác’s craft is that he managed to write a page-turner about a murder that has already been solved. The reader isn’t driven by curiosity regarding who killed the victim but why the murderer did it and how the death affects those around her. Perhaps this contradiction – a mystery that isn’t really a mystery – explains why the book felt simultaneously short and long to me. I read this book in one sitting and speculated furiously about the ending, yet it also felt like it took forever to reach the very satisfying conclusion.

TECHNICAL STUFF

Note for readers: Nguyễn Mộng Giác’s One-Way Street is available online in Vietnamese here: https://nguyenmonggiac.com/duong-mot-chieu.html. You can also listen to it as an audiobook here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Pj9XQ0fZx8. Unfortunately, it has not been translated into English.

Note for researchers: One-Way Street won the annual prize for best novel awarded by the Vietnam PEN Association in 1974 in the RVN. The book would be great for scholars interested in the RVN’s judicial system in the early 1970s, especially court proceedings and the culture surrounding public trials. Keep in mind that this fictional trial takes place before a military tribunal rather than a civilian court because the murderer was a soldier.

The version I read: Nguyễn Mộng Giác. Đường một chiều. Reprint ed. Westminster, CA: Văn Nghệ, 1989.

Photo credit: The image linked to this post shows a street scene from Qui Nhơn before 1975. I found it here: https://www.sbs.com.au/language/vietnamese/vi/podcast-episode/seeds-of-love-200-a-love-story/ruws1ez90.