A ghost from Christmas past! That was my first thought upon laying eyes on the document. I was visiting Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa, and I happened on a memo that recounted a dramatic confrontation at the Hanoi cathdral, North Vietnam, on Christmas Eve over sixty years ago.

Let me back up a little bit. Library and Archives Canada (LAC) is the rather unwieldy name of the national system of research libraries and archives in Canada, and I visited the Ottawa location for the first time in fall 2023 to conduct exploratory research. I was specifically interested in documents produced by the Canadian delegation to the International Control Commission (ICC). The ICC was established in 1954 to oversee the implementation of the Geneva Accords. The accords ended the First Indochina War/Resistance War, Vietnam’s war of independence against France, by dividing Vietnam temporarily into two zones. The communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) regrouped its forces to the northern zone, and the French and the anticommunist State of Vietnam (soon to be renamed the Republic of Vietnam) withdrew its forces to the southern zone. The ICC operated in both zones, North and South Vietnam, and was tasked with investigating alleged violation of the accords by the various sides. The international commission was composed of three distinct delegations representing the different camps of the Cold War. A Polish delegation championed the interests of communist countries, the Canadians represented of the so-called “Free World,” and neutralist India’s delegation chaired the ICC.

With the partition of Vietnam, the DRV became closed off to Westerners from the American-led “Free World.” Very few French, British, and Canadian citizens remained in North Vietnam after 1954, even fewer visited in the late 1950s, and no American that I know of set foot in the DRV in those years. Only the Canadian delegation to the ICC had a sizable and sustained presence in North Vietnam at the time. The international commission had an office in Hanoi and smaller teams located in various cities, and Canada sent diplomats to help staff those locations. Thus, Canadians were among the very few noncommunist Westerners to produce firsthand accounts of the DRV. The officers in the Canadian delegation wrote a steady stream of correspondences to each other as well as the Department of External Affairs back in Ottawa (the equivalent of the American Department of State or the foreign ministry in many countries). These missives not only provided updates about the activities of the ICC but also general observations about North Vietnam. Today, the records produced by the Canadians represent some of the only noncommunist Western account of North Vietnam at the time.

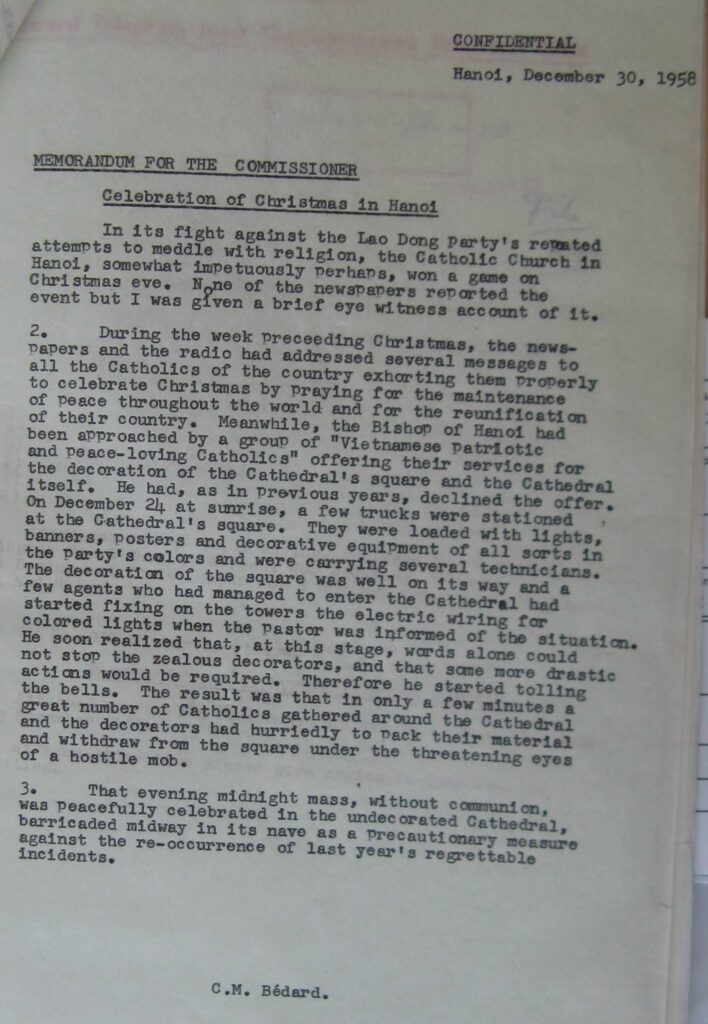

The document that I dubbed the “ghost of Christmas past” was a memorandum written by a Canadian diplomat named CM Bédard, dated December 30, 1958. In it, the diplomat recounts a recent holiday incident between the Vietnamese Catholic church and the Vietnamese Labor Party (Đảng Lao Động Việt Nam), which was then the official name of the Vietnamese Communist Party. The letter writer explained that the party routinely interfered in religious life, and a brief confrontation erupted on Christmas Eve in Hanoi as a result. In the previous weeks, a group of party loyalists calling themselves the “Vietnamese Patriotic and Peace-Loving Catholics” (most likely the Ủy ban Liên lạc những người Công giáo Việt Nam yêu Tổ quốc, Yêu hòa bình) had offered to decorate the interior of the Hanoi cathedral (Nhà Thờ Lớn, St Joseph’s Cathedral) and the adjoining square with party propaganda. Although the bishop declined, the activist Catholics ignored him and arrived at daybreak on December 24 to put up the decorations. Dismayed, the priest sounded the cathedral bells to summon the faithful, and a crowd of believers soon gathered around the building, prompting the “peace-loving Catholics” to flee. This incident, all but forgotten today, represented a particular moment in the longer history of difficult church-state relations in North Vietnam.

What I like about this document is the vividness with which it describes the event. In my mind’s eye, I can see the “peace-loving Catholics” sneaking into the cathedral, hear the pastor urgently clanging the bells as an alarm, and feel the indignation of the crowd as it eyed the intruders. I’ve always felt that archival documents have a magical way of transporting me to the past, though it’s easy to lose sight of that when I feel buried in the boring materials that make up the bulk of my research – meeting minutes, reports, position papers, project proposals, and government correspondences. It sometimes takes an intriguing document like this one to remind me of just how thrilling archival research can be, even thought this particular one has nothing to do with any of my research projects. Also, this memo is the only archival document I have ever encountered in my entire career that is about Christmas.

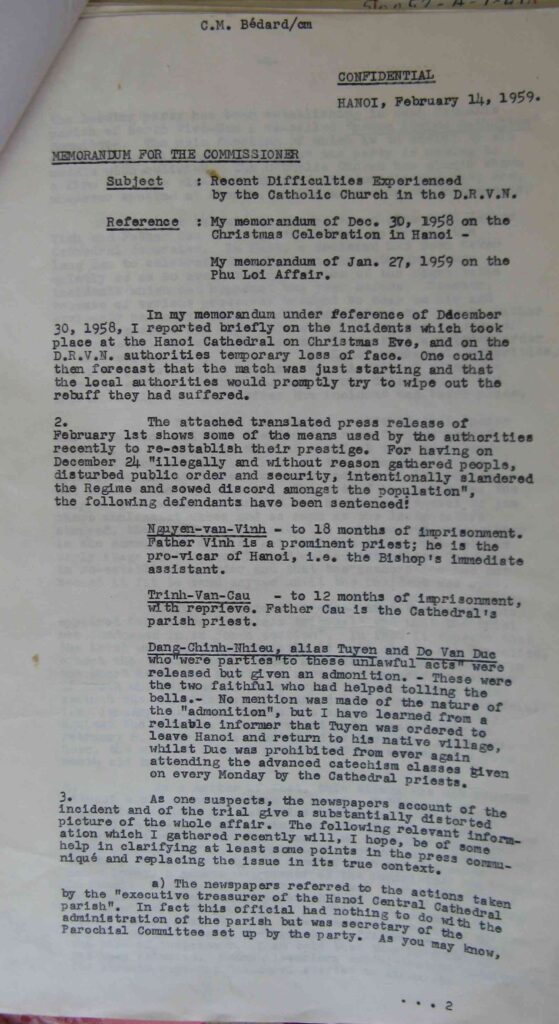

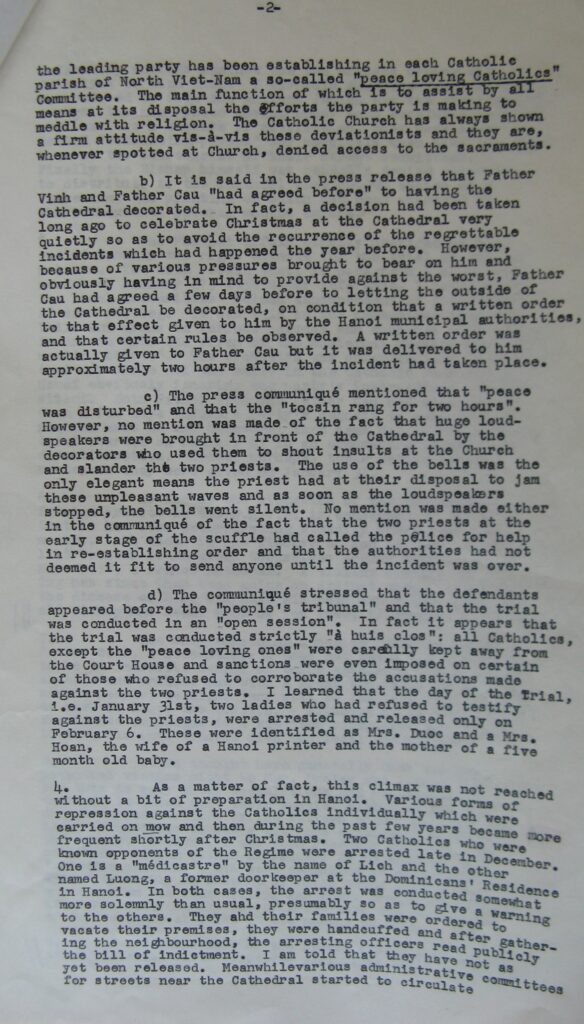

Yet the story of Christmas Eve 1958 in Hanoi did not end with the memo. I discovered a second memorandum dated some six weeks later on Valentine’s Day 1959. This time, Bédard reported that the DRV had tried two Catholic priests in late January in relation to the Christmas Eve incident. After a closed trial, the government convicted them both of a slew of crimes, including illegally assembling a crowd, disturbing public order, slandering the government, and sowing discord among the people. All that for just ringing the bells! According to the memo, the parish priest and the authorities had engaged in extensive negotiations in the weeks leading up to Christmas, and the surreptitious decoration operation of the “peace-loving Catholics” violated the agreement. The diplomat also paints the trial as grossly unjust, with the authorities punishing witnesses who refused to testify against the priests and retaliating against ordinary believers who would not defame their religious leader.

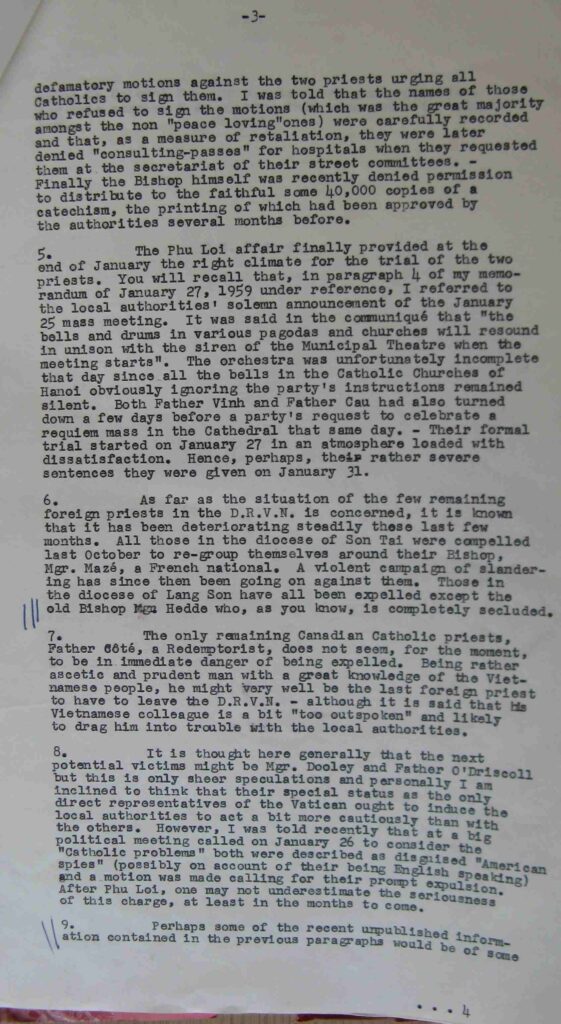

Analyzing an archival document means making sense of the various references that it may contain, and in this case, the second memo notes that the DRV chose to hold the trial of the priests in late January to take advantage of the Phú Lợi affair. Although not explained in the document itself, the Phú Lợi affair was a short-lived prison rebellion that erupted in December 1958 in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, or South Vietnam). Prisoners at Phú Lợi prison, located just north of Saigon, complained about horrendous prison conditions and rose up in defiance against the RVN. Many among the prisoners were members of the communist party and their sympathizers. The DRV held up the uprising as proof of the RVN’s cruelty and oppressiveness. The decision to try the priests in the aftermath of the Phú Lợi incident may have been the DRV’s attempt to link the defendants to the anticommunist regime in Saigon and depict them as sowing division during a time of national resistance.

The second memo ends with the suggestion that its contents should be made available to “Colonel Nam for counter-propaganda purposes.” Again, Bédard offers no explanation, but the recipient would have known that Colonel Hoàng Thụy Năm was the chief of the RVN Liaison Mission to the ICC. The liaison mission was an independent agency within the government of the RVN that compiled complaints regarding North Vietnamese violations of the Geneva Accords, submitted the complaints to the ICC, and responded to similar allegations that the North Vietnamese authorities lodged about the southern government with the ICC. Equally important, the mission produced anticommunist propaganda for the RVN and publicized notorious incidents of communist repression in North Vietnam. Therefore, the author of the missive was actively encouraging the Canadian government to pass on unflattering information about North Vietnam to Hoàng Thụy Năm so that the latter could use it to discredit the DRV. Far from being a neutral observer, the Canadians in North Vietnam were actually quite hostile to the Vietnamese communist party.

Yet there are still mysteries about this Christmas Eve incident that I have yet to solve. According to the first memo, during Midnight Mass in 1958, the cathedral was “barricaded midway in its nave as a pre-cautionary measure against the re-occurrence of last year’s regrettable incidents.” What happened at the Hanoi cathedral in 1957? I don’t know, as I never found any documents about it. Nor did I ever find any additional records about the fate of the convicted priests. I guess those are ghosts of Christmas past that have yet to reveal themselves.

THE TECHNICAL STUFF

Image credit: I found the photo of what I believe is the Hanoi cathedral in 1954 at http://redsvn.net/ngay-giai-phong-thu-do-10-10-1954-qua-60-buc-anh-cua-tap-chi-life/

First memo: Bédard to Commissioner, 30 December 1958, Library and Archives Canada, Department of External Affairs Fonds, RG25-A-3-b, 50052-A-1-40, volume 4639, part 1.

Second memo: Bédard to Commissioner, 14 February 1959, Library and Archives Canada, Department of External Affairs Fonds, RG25-A-3-b, 50052-A-1-40, volume 4639, part 1.

This is the Father Vinh of your report – https://tgpsaigon.net/bai-viet/chan-dung-linh-muc-viet-nam-cha-gioan-lasan-nguyen-van-vinh-44125

He was an amazing person – highly educated and a talented musician.

Good sleuthing! The link provides a biographical sketch of Father Nguyễn Văn Vinh and states that the initial sentence of 18 months turned into a dozen years in prison. He died in prison in 1971, unbeknownst to family, friends, and believers outside of prison. Interestingly, the account does briefly describe the incident in 1957 and on Christmas Eve 1958. According to this account, unnamed people sent by the government put up lights and decorations on or near Christmas in 1957 and then demanded that the church pay them for the labor and materials, but the church refused. When the same thing happened in 1958, Father Trịnh Văn Căn (not Cau, as written in the archival document above) rang the bells in protest, and Father Vinh intervened and eventually put an end to the decoration attempt. So the biographical sketch largely agrees with the version of events in the archival documents but adds some details.