I regularly teach a survey course on the history of Vietnam, and I’m often struck by the stark differences between my introduction to the subject compared to my students. I grew up in a Vietnamese-American household, and I first learned history from my mother, who always taught in Vietnamese. She based her lessons on her own education in the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam, 1955-1975), and the explicit message behind her teaching was that this history was the history of my people. In contrast, most of my students are Americans who are not of Vietnamese heritage. I teach entirely in English, and my syllabus often reflects the English-language scholarship. Most importantly, my students largely regard Vietnamese history as the history of a foreign country, and they have a profoundly different relationship to the Vietnamese past than I did.

My mother learned and passed down to me a very nationalist version of history that proudly celebrated Vietnam’s heroic struggle against foreign aggression. When I was about five or six years old, she began giving me short readings about the first period of premodern Vietnamese history, conventionally known as the “1000 Years of Northern Domination” (Một ngàn năm Bắc thuộc). The rather dramatic moniker describes the millennium from 111 BC to 939 AD when northern Vietnam was part of the Chinese empire. The readings recounted what seemed like an endless string of anti-Chinese rebellions: the uprising of the Trưng sisters against the Han dynasty in 40 AD, Lady Triệu’s resistance against the Eastern Wu in 248, Lý Bôn’s rebellion against the Liang dynasty in 541, Mai Thúc Loan’s rebellion against the Tang dynasty in 722, and many more. The various episodes blended together in my childish brain to convey a simple lesson: the Vietnamese were indomitable in their resistance to Chinese oppression. When I was about ten years old, my mother began providing more formal instruction. She organized weekend language classes in our home, and my classmates consisted of a family friend and later two cousins. History was one of the core subjects, and she covered it at least once a month. Although her classes increased in complexity and difficulty as we became teenagers, the message never changed: we Vietnamese always fought against foreign rule.

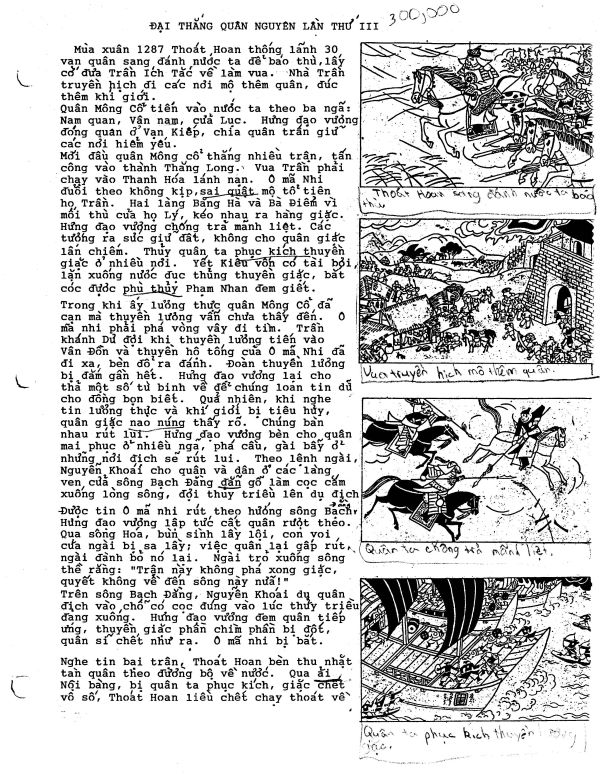

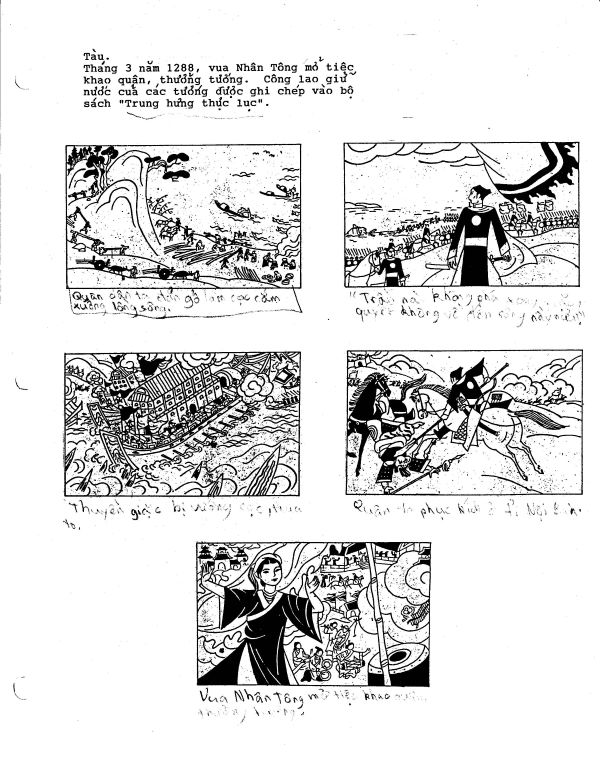

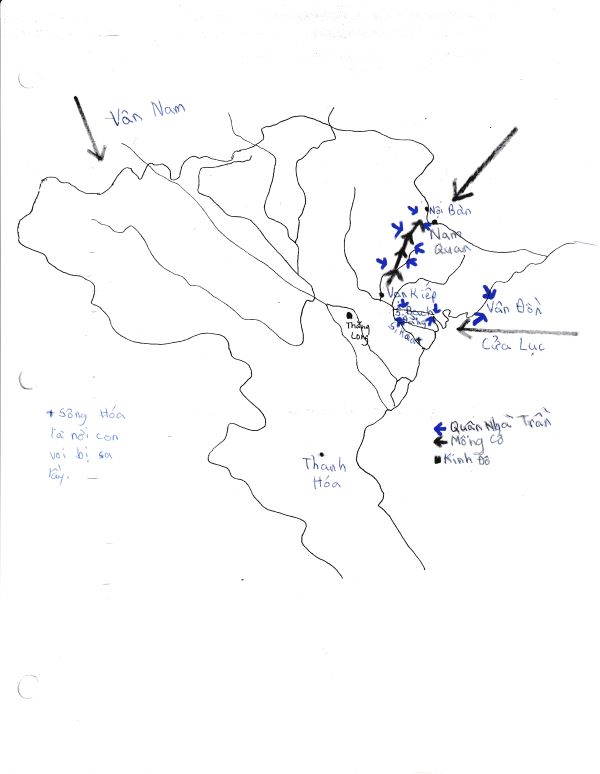

Premodern history, which I am defining here as the period before 1500 AD, especially excited my classmates and me because it made us feel proud to be Vietnamese. We marveled at the military genius of Ngô Quyền, who defeated the (Chinese) Southern Han in the Battle of Bạch Đằng River in 938. Ngô Quyền ordered his men to install iron-tipped poles in the riverbed in anticipation of an attack. The warships of the Southern Han advanced when the tide was high but became stranded on the iron-tipped poles when the tide went out, and Ngô Quyền’s troops easily triumphed over the invaders. It was a spectacular victory that decisively ended the millennium of “Northern Domination” and birthed an independent kingdom. The rule of Ngô Quyền and his descendants proved fleeting, but the kingdom endured and even grew during the Lý (1009-1225) and Trần dynasties (1225-1400). Perhaps my favorite historical event as a child was the Trần-Mongol Wars of the 13th century. The Mongol empire conquered China, central Asia, and Eastern Europe but lost to the Trần kings of Vietnam, my mother emphasized. The highpoint for my classmates and me was the Battle of Bạch Đằng River of 1288, when Trần Hưng Đạo adopted Ngô Quyền’s trick with the iron-tipped poles and roundly defeated the Mongols. Yet another spectacular victory for Vietnam! How brave and clever our ancestors were for outsmarting the invaders!

I think my classmates and I enjoyed these lessons in part because we found it heartening to learn that our people were once winners rather than losers. We came from refugee families that identified with the Republic of Vietnam, which fell to Vietnamese communist forces at the end of the Vietnam War. Our country’s glorious past felt like a salve for the shame of defeat and the indignities of refugee life. With the benefit of hindsight and academic training, I realize that my mother taught a highly flattering interpretation of history that was developed by Vietnamese nationalists during the French colonial period (1862-1945). Just as we wanted to believe that our ancestors were victors, so too did colonial-era intellectuals want to hearken back to a past when Vietnam was free from foreign rule. Research in the last forty years by Keith Taylor, Catherine Churchman, and others have drawn a far more complicated picture of the “1000 Years of Northern Domination.” They have shown that political and military elites that emerged after 40 AD often identified with the Chinese empire rather than considering it to be foreign. These elites often accepted imperial rule when the empire was strong but rebelled and declared their own kingdoms when the empire was weak, similar to ambitious local leaders in other parts of the empire. Moreover, neither the Chinese empire nor premodern Vietnam were recognizably Chinese or Vietnamese as we understand those terms today (and I use “China” and “Vietnam” in this post as easy shorthands to aid comprehension). The Lý and Trần kings certainly defended their kingdoms against foreign invasion, but they were also protecting their own power. The more scholarship I read on premodern Vietnam, the more it became clear to me that those rebellions and wars never formed a consistent pattern of resistance to foreign aggression as I had been taught.

My mother’s handouts and map exercise (with my preteen handwriting)

On a more abstract level, I would argue that my mother emphasized the particularities of Vietnamese history, that is, the aspects of history that appeared to set Vietnamese people apart from the rest of the world. That particularistic approach appealed to my classmates and me because we wanted to think that our ancestors were special. Accordingly, my mother’s lessons were replete with details about specific kings, generals, and battles. It was presumably these details that distinguished us as a people. (Many, but not all, scholars consider nationalism to be particularistic rather than universal.) But the problem with this approach is that it makes Vietnamese history parochial. Why should anyone who’s not Vietnamese care about Vietnamese history if it has nothing to do with the rest of the world? Leaving behind the nationalist version that I had grown up with, I came to believe that studying history should be about exploring humanity’s past and not about feeling good about any particular group of people.

Now, as a professor, I find that my students’ relationship to Vietnamese history couldn’t be more different from mine as a teenager. If I tried to cover every single rebellion during the “1000 Years of Northern Domination,” my students would probably fall asleep at their desks rather than thrill at the idea of Vietnamese resistance. Nor do they especially care about Ngô Quyền or Trần Hưng Đạo’s military genius. The two Battles of Bạch Đằng River are interesting anecdotes but hardly pique their interest enough to merit detailed coverage in my lectures. As far as I can tell, my students think of premodern Vietnamese as just another group of people who lived a long time ago in a faraway country, and they are more interested in Vietnam as a case study for understanding the universal human experience than as an ancestral past.

Therefore, I emphasize universality rather than particularity in my teaching. I present premodern Vietnam as facing the same challenges as all human societies, and my unit on that period emphasizes the problem of political legitimacy. I explain to my students that all human societies grapple with similar questions: Who should rule our society? How do we encourage our rulers to be just, reasonable, and compassionate rather than violent, arbitrary, and cruel? How do we ensure peaceful transitions of power? During lecture, I point out that it is not in the interest of any society to be ruled by a tyrannical mass murderer or to risk all-out warfare every time there is a transition between rulers or regimes. I even make a comparison to the modern US. Today, Americans subscribe to the ideal of democracy, and politicians appeal to those ideals when they make arguments about who should hold office, what policies the government should pursue, and how elections should be carried out. Indeed, politicians present themselves as democratic even when they are not in order to appear legitimate. Similarly, elites in premodern Vietnam subscribed to a mixture of Confucianism, Buddhism, and animism and appealed to those ideas to justify their ambitions and policies. My students come to understand that premodern Vietnam wrestled with universal problems that continue to confront all human societies, even the one in which they are living. I believer it is ultimately such universalities that make Vietnamese history meaningful to my American students.